Introduction

For older struggling readers, the ability to read proficiently can significantly impact academic success and self-esteem. Research in educational psychology suggests that utilizing high-interest low-level (HILL) reading passages can be a strategic approach to address the challenges faced by these learners (Brozo et al., 2007). HILL passages are texts with engaging content written at a readability level suitable for struggling readers, providing a powerful method to marry student interest with learning need, thus aligning with the fundamental principles of the science of reading.The Science of Reading: An Insightful Perspective

The science of reading represents an evidence-based framework focusing on how individuals learn to read, encompassing phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary development, reading fluency, and comprehension (National Reading Panel, 2000). This robust approach offers insights into developing instructional strategies that can address the diverse needs of learners, especially older struggling readers.

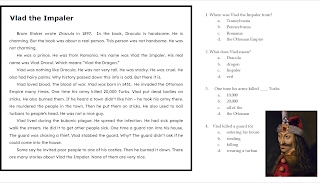

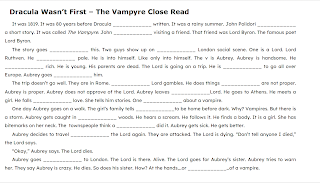

- Free High Interest Low Level Reading Passages - Vampires for Halloween

- Free High Interest Low Level Reading Passages - Native American-Themed

- 56 - High Interest Low Level OCTOBER-FALL Themed Reading Passages

- Native American High Interest Low Level Native American Themed Reading Comprehension and Fluency

- 20 High Interest Low Level Passages - Hauntings

- Mary Shelley's Frankenstein in High Interest Low Level Passages

The Rationale for High-Interest Low-Level Passages

1. Motivation and Engagement

Lack of motivation is a significant barrier to reading for older struggling readers (Guthrie et al., 2013). HILL passages aim to rekindle interest and curiosity, aligning content with students' preferences and experiences, and thus, fostering intrinsic motivation and sustained engagement in reading tasks. Students engage when reading about influencers, the latest trends, superheroes, mystery and other high interest topics.

|

| Link to this Resource |

They also love feeling like they belong - reading what others are reading - like novels adapted to High Interest Low Level fluency and comprehension passages. Here is an example for one such resource centered on Mary Shelley's Frankenstein.

2. Building Confidence and Competence

Accessible content allows students to experience success, enhancing their self-efficacy and promoting a positive reading self-concept (Bandura, 1997). This success cycle can bolster the willingness to engage with more challenging texts over time.

3. Reinforcing Comprehension and Vocabulary

HILL passages, with their engaging and relatable content, provide a context for students to acquire new vocabulary and improve comprehension, paving the way for a smoother transition to complex texts (Cunningham & Stanovich, 1998).

Strategies for Integrating HILL Passages

1. Selection of Appropriate Texts

Identifying texts that resonate with students’ interests and are at an appropriate readability level is crucial (Ivey & Broaddus, 2001). These should offer cognitive engagement while avoiding frustration due to complexity.

2. Multimodal Learning Integration

Blending HILL passages with multimodal resources such as visuals and interactive media can enrich the learning experience and cater to diverse learning preferences (Mayer, 2001).

3. Regular Assessment and Feedback

Continuous assessment and constructive feedback are vital for adjusting instructional strategies to meet individual learning needs and facilitate progressive development in reading proficiency (Black & Wiliam, 1998).

4. Fostering a Supportive Learning Environment

Creating a classroom atmosphere that values diversity, inclusivity, and mutual respect is fundamental. This supportive ambiance encourages risk-taking, cooperation, and mutual learning (Cohen et al., 2004).

Empirical Evidence Supporting HILL Passages

Studies emphasize the efficacy of high-interest texts in mitigating reading difficulties. A study by Guthrie and Humenick (2004) highlighted that engaging texts significantly improved reading comprehension and overall motivation among struggling readers. Similarly, research by Hidi and Harackiewicz (2000) supported the correlation between interest and academic achievement, reinforcing the potential of HILL passages in enhancing learning outcomes.

Benefits and Potential Outcomes

Improved Reading Proficiency Frequent interaction with accessible texts facilitates improvement in essential reading components, creating proficient and fluent readers (Krashen, 2004).

Enhanced Learning Experience HILL passages can transform reading from a burdensome task to an enriching and enjoyable activity, promoting a lifelong passion for reading and learning.

Boosted Academic Performance Enhanced reading skills and increased motivation translate into improved academic achievement across disciplines and contribute to a more positive learning experience (Schiefele et al., 2012).

Conclusion: A Pedagogical Paradigm Shift

Incorporating high-interest low-level reading passages is paramount in constructing an inclusive, learner-centered environment, addressing the multifaceted needs of older struggling readers. This approach, underpinned by the science of reading, fosters academic growth, cognitive development, and a positive learning disposition.

Get this resources at: High Interest Low Level Vampires.

References

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Freeman.

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Assessment and classroom learning. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 5(1), 7-74.

Brozo, W. G., Shiel, G., & Topping, K. (2007). Engagement in reading: Lessons learned from three PISA countries. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 51(4), 304-315.

Cohen, E. G., Lotan, R. A., Scarloss, B. A., & Arellano, A. R. (2004). Complex instruction: Equity in cooperative learning classrooms. Theory into Practice, 43(1), 56-65.

Cunningham, A. E., & Stanovich, K. E. (1998). What reading does for the mind. American Educator, 22(1-2), 8-15.

Guthrie, J. T., & Humenick, N. M. (2004). Motivating students to read: Evidence for classroom practices that increase motivation and achievement. In P. McCardle & V. Chhabra (Eds.), The voice of evidence in reading research (pp. 329-354). Brookes.

Guthrie, J. T., Wigfield, A., Metsala, J. L., & Cox, K. E. (2013). Motivational and cognitive predictors of text comprehension and reading amount. Scientific Studies of Reading, 3(3), 231-256.

Hidi, S., & Harackiewicz, J. M. (2000). Motivating the academically unmotivated: A critical issue for the 21st century. Review of Educational Research, 70(2), 151-179.

Ivey, G., & Broaddus, K. (2001). "Just plain reading": A survey of what makes students want to read in middle school classrooms. Reading Research Quarterly, 36(4), 350-377.

Krashen, S. (2004). The power of reading: Insights from the research. Libraries Unlimited.

Mayer, R. E. (2001). Multimedia learning. Cambridge University Press.

National Reading Panel. (2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Schiefele, U., Schaffner, E., Möller, J., & Wigfield, A. (2012). Dimensions of reading motivation and their relation to reading behavior and competence. Reading Research Quarterly, 47(4), 427-463.